Academy trusts are launching women-only leadership programmes, promising flexible working and overhauling recruitment advertising to attract more men into “traditionally female” roles to drive down gender pay gaps.

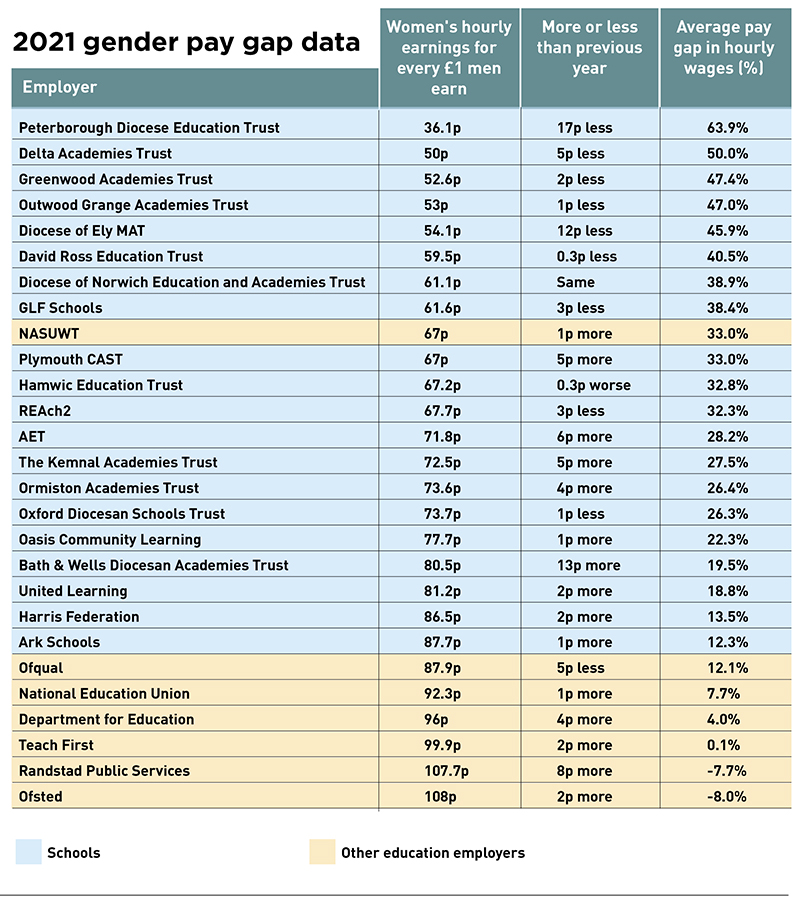

Schools Week analysis shows gaps narrowed at the largest trusts in 2020-21 – but on current trends it will take 22 years to close them altogether.

Alice Gregson, the chief operating officer at the trust support group Forum Strategy, said it painted a “worrying picture” with education lagging behind other sectors. But trusts argue that the data is flawed.

Pay gap closes – but still 26%

Large employers have had to publish median male and female pay per hour since 2018.

Among the 20 biggest trusts, women lag behind men by 26 per cent, but it marks a 1.2 percentage point improvement year-on-year.

The gaps narrowed in half of the trusts, one stayed the same and nine worsened.

The Bath & Wells Multi-Academy Trust improved most: its gender pay gap decreased from 32.1 to 19.5 per cent.

Nicola Edwards, its chief executive, said more women had been encouraged into middle and senior leadership. It now anonymised applications, and ensured gender-balanced recruitment panels.

The Harris Federation’s gap narrowed from 15.9 to 13.5 per cent, the second lowest.

Sir Dan Moynihan, its chief executive, said it remained “bigger than it should be”, but highlighted Harris’ efforts to recruit women on to its two-year “accelerated principal” programme.

“Half the battle is building confidence,” he said.

Trusts point to flexible working policies

Outwood Grange Academies Trust (OGAT), whose gap was the fourth largest, but narrowed slightly, runs a leadership course that is open to women in all roles.

Many participants have since been promoted, said Katy Bradford, the trust’s chief operating officer.

Ark Schools, with the smallest gap at 12.3 per cent, highlighted its female-dominated management, efforts to “incorporate part-time and flexible workers”, and a new diversity and inclusion manager post.

Bath & Wells said flexible working and parental leave policies had boosted female leadership and male take-up of support staff roles.

The Peterborough Diocese Education Trust (PDET) needed to attract more men into primary education support roles, its report said. It highlighted calls by MPs for better leave for fathers.

United Learning reformed the wording and imagery on recruitment advertising to attract not only women into leadership and facilities jobs, but also men into “traditionally female” teaching assistant and primary teaching roles.

Women make up 74 per cent of top earners at large trusts – but 91 per cent of the lowest earners too.

Female dominance of lower-paid jobs key factor

Education has the third highest gap among all sectors, with trusts making up nearly half of the 50 large UK employers with the biggest gaps.

Many trusts attribute the large gap to more women in lower-paid roles. Ark, for instance, has said that a “dearth of men” in lower-paid roles explained two-thirds of its gap.

Leora Cruddas, the chief executive of the Confederation of School Trusts, said closing gender gaps was taken “incredibly seriously”. But role-by-role comparisons showed “far less dramatic” divides.

OGAT’s headline gap was 47 per cent. But among teachers the pay gap was only 0.1 per cent, the trust said.

Many trusts said reviews showed no gap between staff doing the same jobs, and highlighted salary bands set nationally or locally.

Methodology “artificially inflated” gaps more, Bradford said.

For instance, the hourly rate for teachers was calculated over 38 weeks, but over 52 weeks for support staff.

Ruth Walker-Green, the chief executive of PDET, said: “We don’t believe headline figures fairly reflect the inclusive nature of the trust.”

Julie McCulloch, the policy director of the Association of School and College Leaders, said women’s earnings were affected disproportionately by part-time work and career breaks to provide family care.

But Vivienne Porritt, the co-founder of WomenEd, said trusts should acknowledge leadership recruitment and pay issues too.

Three-quarters of teachers are women. But this drops to two-thirds for heads and just a third of the best-paid chief executives, according to Schools Week’s annual analysis.

WomenEd research suggests seniority widens division, with a 11.3 per cent gap for heads, quadruple that of teachers.

But while there is almost no gap for maintained secondary heads, the gap for academy secondary leaders widened to £3,399 last year.

Union that campaigned on gender pay has huge gap

But it’s not just academies that have large pay divisions.

The teachers’ union NASUWT had a significant 33 per cent gap among staff, compared with 7.7 per cent at the National Education Union.

The NASUWT, which recently said misogyny blighted members’ pay progression, pledged “further action”, including gender balance at every salary quartile.

Both unions highlighted equalities training for managers and improved recruitment processes.

The Department for Education fared better at 4 per cent, although the gap widened among its senior staff.

Meanwhile, women who work for Ofsted and the National Tutoring Programme provider Randstad earn more than men.

Teach First has also nearly eradicated its gap – it fell to 0.1 per cent – after moving hiring decisions from managers to a trained, diverse “assessor community”, and recruiting more female managers.

Porritt said organisations should not see reports alone as “complying”, instead co-developing action plans with staff.

Mandy Coalter, the founder of the HR consultancy Talent Architects, said breaking down gender stereotypes, however difficult, could address pay gaps – and staff shortages.

Your thoughts