5 Reasons To Be Hyped For Kaito Ono’s Debut Against Marat Grigorian At ONE 172

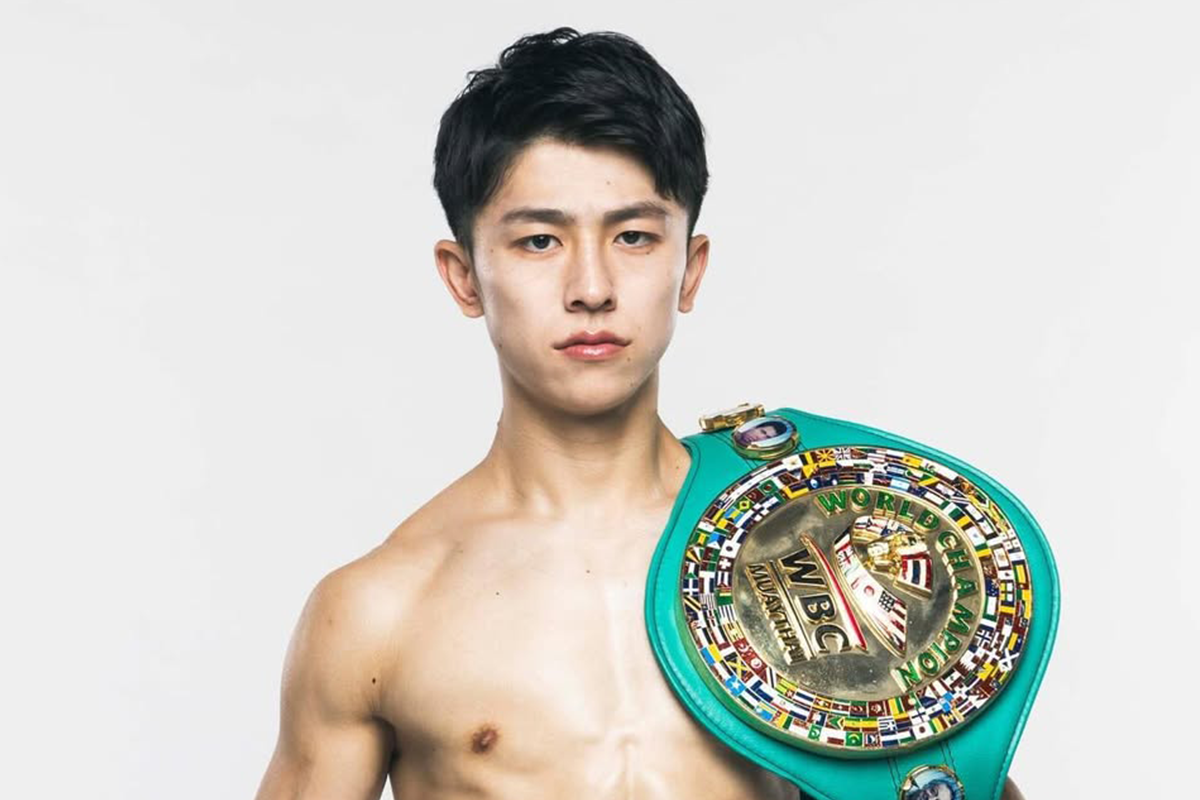

Accomplished Japanese striker Kaito Ono is eager to turn heads when he makes his ONE Championship debut ONE 172: Takeru vs. Rodtang.

On Sunday, March 23, the 27-year-old will step up for the biggest fight of his life against legendary Armenian knockout artist Marat Grigorian in a featherweight kickboxing clash in front of a home crowd at Japan’s Saitama Super Arena.

While Kaito is already well-known among Japanese fans, he has yet to properly introduce himself to ONE’s massive international fan base. He knows that a victory over a decorated striker like Grigorian would quickly propel him into superstardom and the ONE Featherweight Kickboxing World Title picture.

Before he takes to the ring at ONE 172, we take a closer look at what makes Kaito so special – and why fans won’t want to miss his high-stakes debut.

#1 He Started In Karate

Like other elite Japanese kickboxers, including former ONE Bantamweight Kickboxing World Champion Hiroki Akimoto and ONE 172 headliner Takeru Segawa, Kaito started his martial arts journey in karate – a unique style of striking that remains the foundation of his game.

He competed early and often in full-contact karate tournaments at the national level and found plenty of success as a youngster, setting the tone for an impressive professional kickboxing career.

#2 He Has More Than A Decade Of Elite Experience

Although he’s not yet 30 years old, Kaito already boasts an incredible 68-fight professional career that dates back to 2014.

Notably, he has been competing at an elite level for essentially his entire career, honing his skills and developing veteran savvy for more than a decade.

That wealth of experience will surely serve him well against former ONE World Title challenger Grigorian and any other strikers he’ll face in the world’s largest martial arts organization.

#3 He Dominated The Japanese Kickboxing Circuit

Japan’s kickboxing scene is arguably the toughest regional circuit on the planet, and Kaito has spent the past several years racking up titles, trophies, and belts around his home nation.

He won his first regional title at just 16 years old and would go on to claim titles in Shoot Boxing, Rise, and Rebels, cementing himself as one of Japan’s preeminent kickboxers – and erasing any doubts that he is ready for the global stage.

#4 He Owns Multiple Victories Over ONE Superstars

Kaito’s lengthy and impressive career record includes a number of key wins over both former and current ONE stars, including Georgian kickboxing standout Davit Kiria, former ONE Muay Thai World Title challenger Pongsiri PK Saenchai, and fellow Japanese sensation Masaaki Noiri, who will challenge for the ONE Interim Featherweight Kickboxing World Title at ONE 172.

Those victories not only prove that Kaito can compete with the best of the best but also that he owns the necessary skills to take out Grigorian in his promotional debut.

#5 He’s Never Been Knocked Out

After more than 10 years and nearly 70 fights of professional experience, Kaito has never once been finished.

His toughness, granite chin, and superhuman durability should serve him well against the featherweight kickboxing division’s notoriously heavy hitters, including a massive puncher like Grigorian.